Facts About WWE Magazine Only Hardcore Fans Know

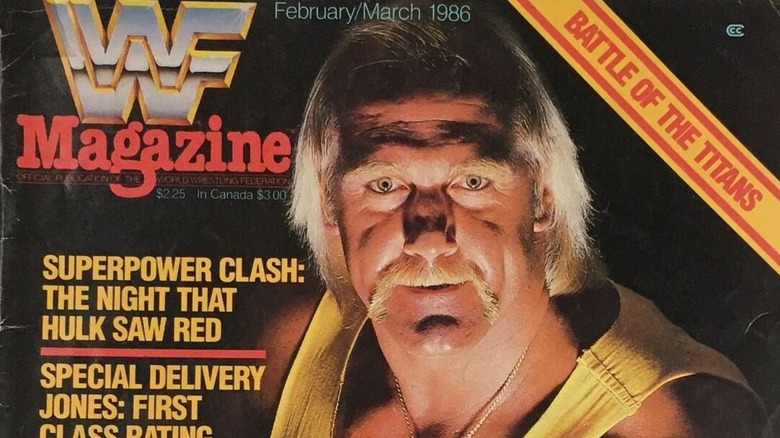

For over 30 years, from 1983 to 2014, WWE Magazine was available everywhere magazines were sold, allowing easy access to all sorts of cool photos, company merchandise catalog, and an odd array of articles that were often childish. It grew with the international expansion of what was then the WWF, fighting a war with the various independently-owned wrestling magazines while Vince McMahon was also battling the promoters whose theoretical turf he was invading everywhere. If you wanted high quality, relatively up to date photos of WWF wrestlers and matches, WWF Magazine was the publication to buy.

As an extension of a notoriously idiosyncratic company, there are, of course, some stories to tell that happened along the way. So let's take a look at some of the more notable ones from throughout the history of WWF Magazine, featuring everything from courtroom battles to sending get well cards to a dog.

The magazine briefly launched a series of hit pieces on WWE's enemies

In 1991 and 1992, a number of different, sometimes interconnected scandals struck the WWF, dealing mainly with steroid abuse and sexual misconduct. With the scandals came lawsuits, initiated by both the company and its critics, and with lawsuits came the discovery process, where each side can make surprisingly broad requests of the other side for documents that may be relevant to the case. For a time in 1993, the WWF seemingly sought to weaponize this information, resulting in a notice in the August issue of WWF Magazine stating that since "we have been subjected to tactics bordering on McCarthyism," they would start to give their side in the next month's issue.

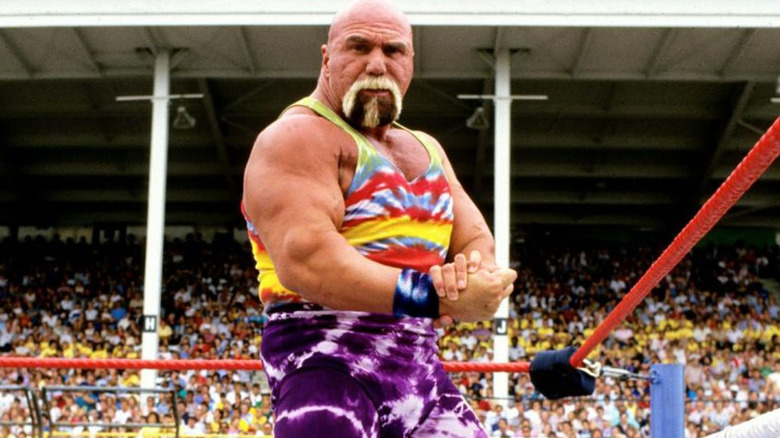

The first edition of "Now It's Our Turn," which would soon be filed in court as an exhibit to a different lawsuit, dealt with "Superstar" Billy Graham, who had sued the WWF along with the manufacturers of various steroids that damaged his health. Most memorably, the article, which ran without a byline, claimed that Graham, despite years as a star wrestler, "has never held a regular job", which gives you an idea of the overall tone. Though the end of the article implies a conspiracy orchestrated by Graham and promises to get into their side of other disputes in the coming months, there was never a second article. It may not be a coincidence that, weeks after the Graham article was published, it was referenced in letters between lawyers for the WWF and the New York Post that were soon filed in court.

WWF Magazine's launch led to the WWF banning third party magazine photographers from ringside

In 1984, the national expansion of the WWF included a bigger push of the recently launched WWF Magazine, and that included stifling the competition. If you were a fan at the time, you may have noticed how the quality and breadth of the photos from WWF events in third party magazines declined overnight. That's because they were banned from shooting ringside, forcing them to either use older archival photos or shoot from the stands using a telephoto lens. "There is a story that sounds apocryphal, I believe it's not, of one of our photographers smuggling the camera into Madison Square Garden like it was a hero sandwich," Craig Peters, formerly of the Pro Wrestling Illustrated family of magazines, told Pop Matters in 2017. "Like the lens was inside the bread of the sandwich and then the body of the camera was stuffed down his pants."

In the October 1984 issue of The Wrestling News, which had previously handled publication of the programs sold at WWF events, editor Norm Keitzer recounted some of his experiences with the refocused WWF. Specifically, he recalled Vince McMahon demanding that The Wrestling News proper only cover the WWF, followed by a promise to put him out of business if he refused. Keitzer also backed up the stories of photographer press passes being done away with at WWF shows, but he added a particularly curious little wrinkle. "[McMahon] recently had his lawyers serve us notice demanding, among other things, that we not publish photos of Hulk Hogan in our magazine because he had granted exclusive publicity rights to [WWF parent company] Titan Sports," wrote Keitzer.

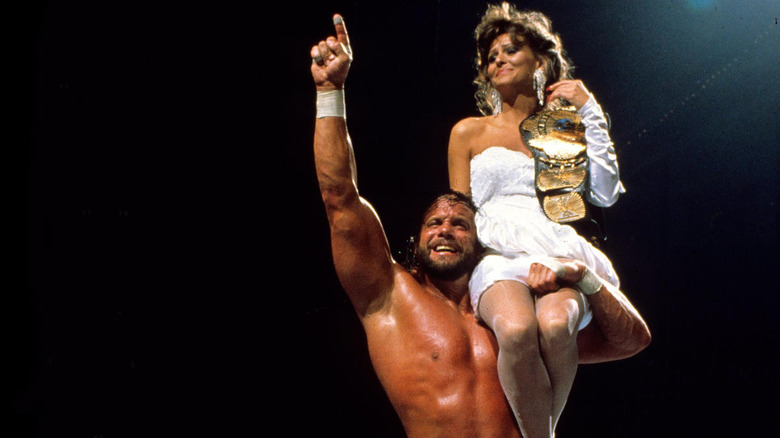

They accidentally spoiled Randy Savage winning the WWF Championship at WrestleMania IV

On March 28, 1988 at WrestleMania IV, Randy Savage won a one-night, single-elimination tournament to become the new WWF Champion. If you were a subscriber to WWF Magazine, though, you knew this was coming for weeks. The issue cover dated April 1988 included a story about Savage's manager, Miss Elizabeth, that referred to her as "manager of World Wrestling Federation Champion Randy 'Macho Man' Savage." Oops. That kind of high profile gaffe was enough for the story to get mainstream news coverage, hitting the front page of the Milwaukee Sentinel on March 17 and being syndicated to other newspapers via the Associated Press. According to the Sentinel article, the issue in question was mailed out to subscribers on February 29, a full month before WrestleMania, but withheld from retailers after the error was spotted.

"Unfortunately, there was a typographical error," WWF vice president of marketing Basil DeVito told the Sentinel. "It is an error which we have noted and a number of interested fans have phoned in about it. A lot of people have called. It's obviously a mistake. It's a typographical mistake." After further prodding, DeVito added that "You're making more out of this than it is." However, in the March 28 issue of his Wrestling Observer Newsletter, Dave Meltzer reported that the WWF "is going insane about the result being public knowledge."

Subscriptions increased dramatically around WrestleMania III

On March 29, 1987, WrestleMania III was a massive success for the WWF, easily the biggest pro wrestling card of all time up to that point, destroying all known records for live attendance, closed circuit television attendance, and pay-per-view television buys. It had a huge effect on the WWF's business as a whole, and it can easily be inferred that the increasing success of WWF Magazine was one of them.

According to the November 30, 1987 issue of Southern Connecticut Business Journal, WWF Magazine's subscriber count went up 54.6% in the first six months of 1987, settling at 212,890, good enough for fourth place among American magazines. Newsstand/retail circulation, meanwhile, went up 36.4% to 93,087. All told, the two data points put together were good enough for WWF Magazine to rank tenth in the country for "overall growth."

"The magazine parallels what goes on in the live events and attendance there has grown steadily since about 1985," WWF Magazine subscription director Jean Abbott told the Journal. "But the popularity of the magazine is coming from our increased professionalism and efforts to give readers what they want."

It was the conduit for Randy Savage's last direct involvement with WWE

Randy Savage's almost complete lack of contact with the WWF/WWE after his 1994 departure from the company has become the stuff of legend. There are no real answers to latch onto, just urban legends of dubious provenance. This leads to hunting for clues, one of which was, for years, the nature of Savage's last direct collaboration with the company. Though deals for his inclusion in action figure lines and video games did materialize, those weren't direct deals with WWE. This led internet detectives to the last involvement he had with WWE before those projects: An interview that he did with SmackDown Magazine for the Holiday 2003 issue.

It wasn't until October 2021 that it became clear that the timing might not be that significant to Vince McMahon or other WWE brass. That was when former WWE Magazine writer Brian Solomon explained on the "6:05 Superpodcast" (h/t Wrestling News Source) that the 2003 Savage interview was just a byproduct of how under the radar the publications division was at WWE. "I remember even in the middle of the interview, he said, 'Does Vince know you're talking to me?'" recalled Solomon. "I'm like, 'No, he has no idea.' He started laughing his ass off because even he couldn't believe that I was doing that."

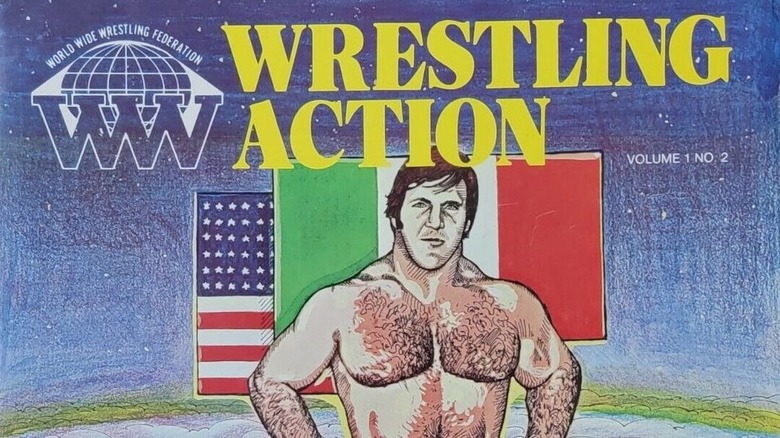

WWF Magazine wasn't the first WWF magazine

Though the publication best-known as WWF or WWE Magazine is easily the most well-remembered of WWE's various periodicals, thanks to its 30 years of publication, it was not actually the first such publication from the promotion. Before Vincent Kennedy McMahon bought out his father, Vincent James McMahon, the elder McMahon's World Wide Wrestling Federation had its own magazine: WWWF Wrestling Action, which debuted in 1977.

The best available history of WWWF Wrestling Action comes from editor Les Thatcher via a post at the highly informative JW's Wrestling Memorabilia blog. That blog notes that Wrestling Action followed in the footsteps of other promotion-specific magazines being published by Thatcher, a jack of all trades in the wrestling business. With Les at the helm, the magazine had a very distinct look, as art director Cal Byers created hand-drawn covers for each issue and George Napolitano's ringside photography was often showcased in color on the magazine's slickly printed pages. At the time, slick pages and color photos between the covers were rare to nonexistent in the newsstand wrestling magazines, which used black ink on pulpy paper.

Why it ended is not clear, though a note in the consumer advocacy column in the April 14, 1978 issue of Pennsylvania's Sunbury Daily Item newspaper alludes to subscriptions not being properly fulfilled and the magazine's post office box going dormant by June 1978.

Vince McMahon tried to use the magazine to rewrite history

WWE's relationship with wrestling history is complicated at best, something best exemplified by some of the tall tales in their documentary productions, like the claim that Vince McMahon changed the company name to WWE without any outside pressure. (As even the official WWE press release from May 2002 notes, it was due to them losing a lawsuit to the former World Wildlife Fund.) Naturally, WWF Magazine, when it was around, was brought into this mix. You got a taste of it earlier with "Now It's Our Turn," but there's more to it than that.

Take, for example, a one page article that appeared in the June/July 1985 issue, titled "The Atlanta Connection," by Jean Manning, who covered wrestling for Atlanta radio station WGST. The article, in trying to frame the WWF's invasion of the Georgia territory as an overwhelming success, sticks to the "technically true" way of telling a story: Very little in the way of substantive details are given, and when it seems like they are, they're not quite what they seem. "Before long, Atlantans who had never before seen a wrestling match in the flesh were turning up at the Omni, packing into its 17,000 seats," wrote Manning.

Read that closely: You get the suggestion that the Omni shows were selling out, but it doesn't actually say that, just that there are 17,000 seats and fans packed into some of them. Though we don't have attendance figures for every WWF show at the Omni, the ones that do have such data on the '80s Omni results page at TheHistoryOfWWE.com aren't particularly promising, ranging from 900 to 9,000 in the year after the WWF entered the market. Ratings data collated by Babyface v. Heel show that the viewership of their takeover of Atlanta's Superstation WTBS, which aired nationally on cable, had a similarly up and down response.

WWF letter-writing campaigns were just ways to build their mailing list

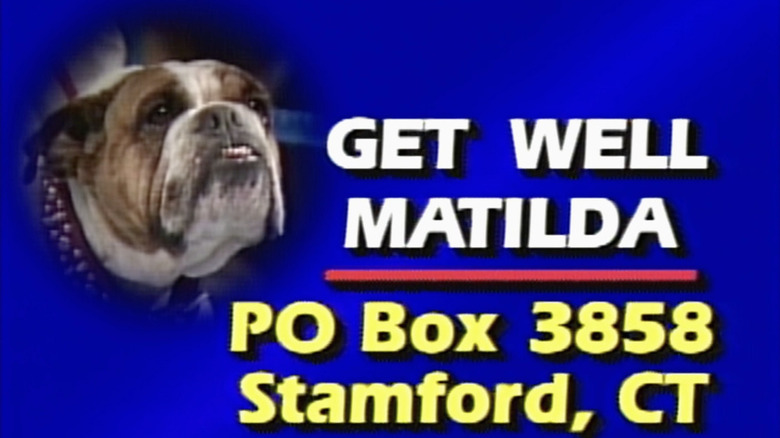

Fans of the WWF from the peak of Hulkamania may recall occasionals calls to action from the promotion, asking the fans to send in letters after a major angle. For example, in 1990, there was Earthquake injuring Hulk Hogan on the set of The Brother Love Show, which led to emotional pleas for "GET WELL HULK" and "COME BACK HULK" letters from Hulkamaniacs around the world. (Consider the source, of course, but at a meet and greet in Somerville, Massachusetts several weeks later that's preserved on YouTube, Hogan claimed to have gotten "over 200,000 letters the first two weeks from all these kids.") Perhaps most memorably, though, at the end of 1987, The Islanders dognapped The British Bulldogs' mascot, Matilda, leading to requests for "GET WELL MATILDA" letters that aired on WWF programming after the Bulldogs got her back.

Why was all of this happening? For the answer, we go to the February 1, 1988 edition of Dave Meltzer's Wrestling Observer Newsletter. "[I]s there anything so absurd as this Get Well Matilda stuff?" he wrote. "It's actually a way to build up [the WWF]'s mailing list for its new line of souvenirs." Yes, it was a way to get the merchandise catalog that came in every issue of WWF Magazine out to fans who didn't read the magazine. The 1988 catalog in question, naturally, included items like a plush Matilda toy and a Matilda t-shirt that was modeled by an 11 year old Stephanie McMahon.

There was briefly a WWF counterpart to the insider wrestling newsletters

It's not exactly a secret that, before he was a TV writer for the WWF, WCW, and TNA, Vince Russo was the editor of WWF Magazine. It's less well-known that, before he worked for the WWF, he had his own wrestling newsletter. Even more obscure than that, though, is something that he did while editor of WWF Magazine: He started a short-lived faux rival newsletter using his "Vic Venom" heel columnist persona after "Vic" elected to "quit" WWF Magazine over a variety of perceived grievances. With his WWF column being titled The Bite, "Vic's" newsletter was, of course, named "The Bite: Uncensored."

"Also, because I'm the kind of guy that I am, I am sending you the first issue of The Bite—Uncensored!!!, absolutely free!!!" he wrote in his "resignation letter" in the August 1995 issue of WWF Magazine. "What did you ever give away that was free besides those worthless trading cards?" He did not, however, shine a light on the fact that his newsletter and WWF Magazine shared a post office box.

It's not clear if the effort lasted more than one issue, which was just more of the same of what was in WWF Magazine. "Actually WWF could put out a very profitable newsletter if they did it correctly," Dave Meltzer wrote in the July 17, 1995 issue of his Wrestling Observer Newsletter. "[T]he ability to give up the b.s. is virtually impossible within the industry and that's their biggest handicap."

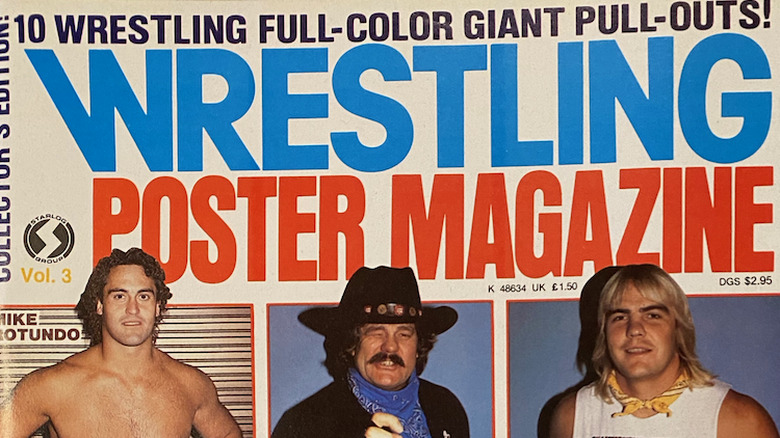

The WWF sued competing magazines for bundling posters with each issue

Remember WWF threatening legal action against The Wrestling News for printing photos of Hulk Hogan that they had full legal rights to because he had "granted exclusive publicity rights" to the WWF? There's a lot more where that came from, as it was part of a campaign of legal threats and lawsuits from the WWF that lasted several years. It didn't just cover the magazine world, either, as Variety reported in its December 25, 1985 issue that the WWF sued Congress Video Group over its "Super Star Wrestling" series of videos, arguing that they implied a false connection with the WWF. (The videos and box art exclusively featured content shot at shows promoted by Jim Crockett Promotions in 1983.)

The legal assault culminated in a precedent-setting case involving rival magazines, though. In 1987, the WWF sued the publishers of the wrestling magazines that were distributed under the Starlog imprint for bundling full-sized posters of WWF wrestlers, with both the district court judge (finding for the defense) and a later appellate panel (finding for the WWF) issuing orders that would be cited as precedent later in other "right of publicity" cases. As the WWF's argument went, the posters being bigger than the average magazine pin-up and their being placed in the center of the magazine without accompanying news content made them a commercial product as opposed to part of a journalistic enterprise. The defense insisted, though, that there was always a corresponding article.

In the district court, that argument got the defense a summary judgment, but that was reversed by the appellate court, reopening the case. It's not clear how the underlying case was adjudicated past it being closed on July 12, 1990.