The Biggest Differences Between WCW And AEW Explained

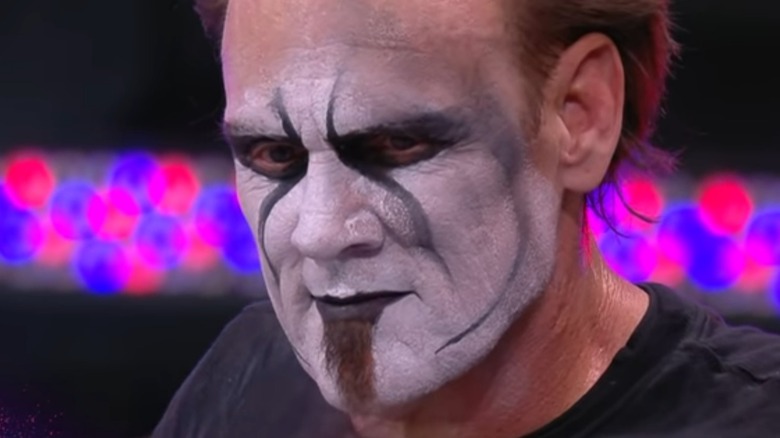

It's 1997. WWE's biggest competitor airs weekly shows on TBS and TNT. Tony Schiavone is on commentary. Sting and Chris Jericho are there too.

It's 25 years later. WWE's biggest competitor once again airs weekly shows on TBS and TNT. Schiavone, Sting, and Jericho are still around. If you hadn't been paying attention to the business for the last couple of decades, you might think that AEW is the continuation of WCW — just an unbroken chain of wrestlers making each other bleed, stretching back to Magnum T.A. and the Road Warriors. But, of course, that's not how things happened.

World Championship Wrestling went out of business in 2001, and WWE bought their tape library, their intellectual property, and some of the wrestlers' contracts. For almost two decades, WWE had no significant competition on the national stage. Sure, there was TNA (now known as Impact Wrestling), but questionable management decisions of their own (as well as WWE's post-WCW air of invulnerability) kept TNA from ever becoming much of a concern.

Then in 2019, billionaire Tony Khan teamed up with a small group of wrestlers to form All Elite Wrestling. They ran their first PPV in May, and by October they had a weekly TV show. Wrestling was back on Turner television, and WWE was no longer the only big game in town.

But just because AEW plays a similar role in relation to WWE and airs on certain channels doesn't mean they're WCW come round again. There are some pretty big differences, so let's take a look at them.

AEW isn't built on the skeleton of another company

AEW was founded after a 2018 PPV event called All In, in which the wrestling faction known as the Elite, who were then associated with New Japan Pro-Wrestling and Ring of Honor, put on an event to rival WWE's just to prove they could. But when Tony Khan teamed up with the Elite to start AEW, it was an all-new company. Most of their talent had worked for other major companies, of course, but everything AEW was to become had to be built from scratch.

WCW didn't start out that way. Ted Turner, the media mogul behind TBS, TNT, Cartoon Network and so on, was too busy reinventing television to build a wrestling company from scratch, so he bought one that was already pretty much built. Jim Crockett Promotions, a wrestling promotion based in North Carolina, had already been expanding throughout the '80s, and their product had already been airing on TBS. In 1988, the Crockett family sold a majority interest in the company to Turner, and WCW was born.

With TV folks in charge, the product would get a lot slicker, but a lot of what made WCW work was already there in JCP: Ric Flair and the Four Horsemen, Dusty Rhodes, Sting, the annual Starrcade PPV (which predated WrestleMania by a couple of years), and a whole infrastructure committed to making a weekly wrestling show.

AEW exists in a very different media landscape

In the mid-'90s, when "WCW Monday Nitro" started to compete with "Monday Night Raw," TV ratings were pretty much the be-all and end-all of media success. Some fans would tape one show on their VCR and watch it later, but what really mattered was what people were watching live. The internet, which for most of the public was just starting to become a thing, wasn't nearly fast enough for watching videos. YouTube was about a decade away, and streaming services wouldn't come along until after that. There was weekly television, analog Pay-Per-View, and print magazines, and that was pretty much it.

Media today is a whole different world, obviously. TV ratings still matter, but not like they once did. For one thing, they've been going down across the board for years, as people's viewing habits change. Some people only watch what's online, and never turn on a TV at all. AEW doesn't have a proper streaming home yet (they'll inevitably find one as their media library grows deeper), but they make extensive use of YouTube. In addition to hosting matches and clips from the shows that air on TV, AEW's YouTube also hosts AEW Dark and AEW Dark Elevation, a third and fourth weekly wrestling show that highlights their lower card and developmental talent. There's also an official AEW podcast, hosted by legendary commentator Tony Schiavone and fan-favorite referee Aubrey Edwards, something WCW couldn't have even conceived of back in the day.

Owner Tony Khan runs AEW himself instead of letting guys like Eric Bischoff run it

Ted Turner was the big boss at WCW, but he was never the day-to-day boss. He wasn't present at regular TV tapings, and he certainly didn't book the cards. He hired guys to do that stuff, most memorably Eric Bischoff, who took charge of WCW in 1993. Tony Khan, on the other hand, takes a hands on approach. He's not just the owner, he's the guy who's there every day, telling the talent what's expected of them and making sure things go the way he wants them to. In that sense, he's actually more like Vince McMahon, wrestling's greatest micromanager, than Turner.

Unlike McMahon, of course, Khan loves not just the idea of wrestling, but everything about what wrestling is in the modern era. Unlike Turner, he's all about getting his hands dirty to put on the best pro wrestling show he possibly can. And unlike Bischoff, Khan has nothing to prove to anybody, and no interest in putting himself over. You'll never see Tony Khan join the Blackpool Combat Club the way Bischoff joined the New World Order. In fact, you'll rarely see him at all — Khan only appears on TV when there's a major real-world announcement to be made.

AEW works to build young stars, instead of only relying on ex-WWE names

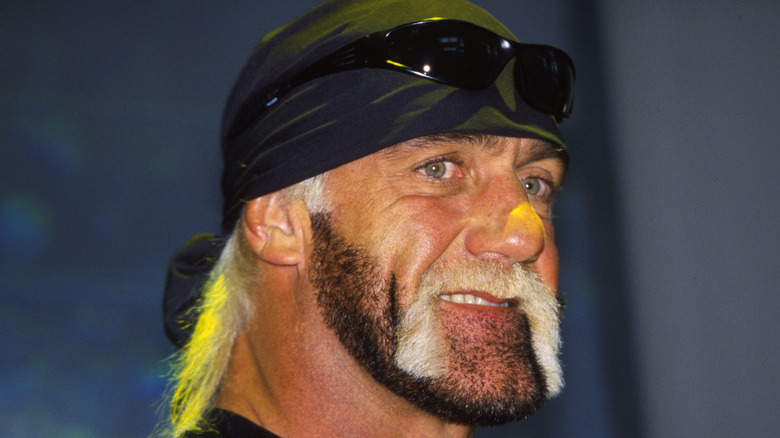

Like WCW, AEW employs a number of former WWE stars. WCW famously had Hulk Hogan, Kevin Nash, and Scott Hall, among others, while AEW has Jon Moxley, Bryan Danielson, Malakai Black, and so on. The problem with WCW was never the presence of ex-WWE personnel, it was the lack of homegrown stars. When you leave aside wrestlers who'd been grandfathered in from Jim Crockett, like Sting and Ric Flair, and wrestlers who would go on to become much bigger stars when they moved on to WWE, like Booker T and Chris Jericho, WCW had very little talent of its own. There was Goldberg, whose WCW run certainly had its problems, and Diamond Dallas Page, wrestling's ultimate every man, and that's very close to the end of the list.

In contrast, AEW has put effort into building new stars from the very beginning. Hangman Adam Page's push toward the AEW World Championship started before there was even weekly TV, and by the time he won just about every fan was cheering for him. Then there's the villainous MJF, and his former bodyguard turned star in his own right Wardlow. Even outside the current main event scene, there's no shortage of up-and-comers who already have considerable followings: Darby Allin, Daniel Garcia, Ricky Starks, Jungle Boy, Sammy Guevara, and plenty of others. There's also the women's division, where ex-WWE stars like Ruby Soho, Toni Storm, and Athena have been roundly outshined by the likes of Britt Baker, Jade Cargill, Thunder Rosa, and Nyla Rose.

The legends in AEW are there to help younger talent

A key part of that star-building process is that Tony Khan and the people who work for him understand the role of elders in wrestling: they're here to get the young stars over. Chris Jericho's number one priority is to help Daniel Garcia, Angelo Parker, and Matt Menard become stars. Before that, he was playing a similar role for Sammy Guevara, Santana, and Ortiz. His feud with MJF was a huge part of helping the latter's popularity as well, but CM Punk also helped with that one.

Similarly, Sting is there to help establish Darby Allin. Jake "the Snake" Roberts, Tully Blanchard, Arn Anderson, and even Vicki Guerrero have all managed acts with the goal of lending a little of their cred to the newer performers, and of course Dustin Rhodes is always ready and willing to lose a match in a manner that will make his opponent look as badass as possible.

That's not to say aging stars never go over in AEW. After all, CM Punk won the World Championship at about the same age as Hulk Hogan was during his WCW run. The important difference is that the veterans holding titles are going to make somebody look like a million bucks when they win the belt in question, something Hogan spent his entire career trying never to do.

AEW doesn't give anyone the creative control that top WCW stars had

The thing about Hulk Hogan is that he rarely did anything he didn't want to do. He was once the biggest star in professional wrestling, and even though that light had dimmed a bit by the time he moved over to WCW in the '90s, he still managed to get creative control over his character and portrayal on the show. If he didn't want to lose a match, he didn't have to. If he hadn't been convinced to turn heel in 1996, nobody could have made him. His partners in the NWO, Scott Hall and Kevin Nash, also had a degree of control, although Eric Bischoff claims it was much less than Hogan had.

In AEW, none of the wrestlers have the company in that kind of creative stranglehold. Even the wrestlers who serve as Executive Vice Presidents of the company, Kenny Omega and the Young Bucks, follow Tony Khan's booking at the end of the day. Major stars like Chris Jericho surely have a conversation with Tony Khan about where things are going for their characters, but everyone understands that it's Khan's decision. Just because AEW lets wrestlers use their own names and gimmicks, unlike WWE, doesn't mean that can do whatever they want. In WCW, at least for some wrestlers at the top, they pretty much could.

There was speculation that Cody Rhodes' departure from AEW involved a conflict over the direction of his character. Cody says it wasn't about that at all, but AEW fans remember when he was getting booed incessantly and absolutely refused to turn heel.

AEW doesn't act like they'll never run out of money

There's another thing that comes up when people talk about leaving AEW: money. We don't know exactly what Cody and Brandi Rhodes were looking for in new contracts, but it seems likely there was an amount of money that could have gotten them to stay with the company. When it comes to MJF's recent issues with AEW, most of the reporting has been about how he wants to get paid more. Perhaps the most important difference between AEW and WCW — at least in terms of AEW's chances of staying in business for the long haul — is that none of these folks have gotten what they wanted. WCW would have given Cody creative control and everybody as much money as they wanted.

Before he was fired by Ted Turner in 1999, Eric Bischoff was known for spending money like it would never run out. He didn't just give wrestlers huge contracts, he also hired musicians like KISS, Megadeath, and Master P, as well as putting money toward weird experiments like the King of the Road Match, in which Dustin Rhodes fought the Blacktop Bully in the back of a truck.

This is where a hands-on owner presumably makes a huge difference. Tony Khan isn't spending somebody else's money, so he's probably a lot more likely to be careful where it goes. That may be frustrating for guys like MJF, but it's a good sign for the future of the company.

AEW is committed to having a women's division

Women's wrestling is one of the areas where AEW has received the most criticism, and it's not unwarranted. Each episode of TV usually features just one women's match, and it's often the shortest on the card. Women wrestlers often disappear from television for weeks or even months at a time, and even Women's World Champions like Hikaru Shida and Thunder Rosa often find themselves with a shocking lack of storylines and televised segments.

However, it's never in doubt that AEW wants to have a women's division and feature at least a couple of those women on every show. They even introduced a women's midcard belt, the TBS Championship, and have used it to push Jade Cargill as a big star. Back in WCW, the role of women was far more up in the air. Obviously, that has a lot to do with the march of history — women's wrestling has seen a huge surge in popularity over the last decade, whereas back in the '90s it was still treated as something of a novelty.

There were attempts to get a women's division going in WCW, usually revolving around Madusa and some combination of visiting Japanese stars, but it was a start-and-stop effort at best. In fact, there was a WCW Women's Championship introduced with a tournament in 1996, but only two women ever held it and it was abandoned by 1998. In 1997 they even introduced a Women's Cruiserweight Championship in association with the Japanese women's promotion GAEA, but that one only had three champions, and was also deactivated in 1998. This was the kind of stop-and-start that could be a problem for WCW in general, but it was far worse for women wrestlers. There were occasional bright spots like Madusa versus Bull Nakano, but many shows had no women's wrestling at all.

AEW doesn't run shows with free admission

One of the most interesting things about watching old WCW shows today is their unusual venues. The first episode of "Monday Nitro," for example, was at the Mall of America. They did regular shows inside Walt Disney World. For other shows, they would set up a ring right on the beach. For several years, they did an annual Pay-Per-View event at the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally, where you could see the bikers sitting around the ring on their Harleys. These kinds of venue choices gave WCW a unique aesthetic, and put live wrestling in front of some people who might not have otherwise watched it.

The only problem is that nobody bought a single ticket to these shows. The Sturgis shows, the Disney World shows, and many of the other WCW events held in unique public spaces had free admission, either to make sure they were full or because there was simply no logistical way to do the show where they wanted and sell tickets. But if you're one of the top two wrestling companies in the country, and especially if you're struggling financially (as WCW very much was in its final years), it would behoove you to charge people admission to your shows. Otherwise, you're just leaving money on the table.

Thankfully, AEW has not brought back this practice for the modern era. Even when they were running shows in front of limited crowds at Daily's Place during COVID, those limited crowds were happily paying for the experience.

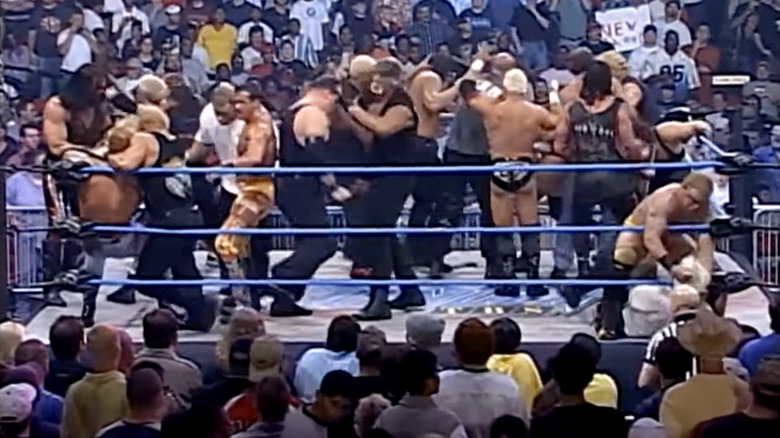

WCW's roster was even bigger

People on the internet love to talk about the size of AEW's roster. "Bloated" is a word you'll hear a lot, although the company mostly seems to do okay once you accept that they consider the YouTube shows an appropriate venue for some talent. Among fans who are looking to criticize AEW, this is an area where WCW comparisons are frequent. Compared to WCW at its worst, however, the AEW roster isn't even all that large.

Depending on how you count day players, announcers, refs, and so forth, AEW has somewhere in the neighborhood of 150 onscreen performers under contract. That's a large number, to be sure, although 2022 has demonstrated how a stacked roster can be a plus when multiple stars are out with injuries at the same time.

Meanwhile, back in 1999, WCW was single-handedly keeping 250 performers employed. No matter how many shows you're running every week, that just sounds like too many wrestlers for a booker to keep up with, not to mention payroll.

AEW never loses track of what wrestling fans want to see

In contrast to WWE's brand of multimedia "sports entertainment," AEW is often seen as the wrestling company for people who love a more pure style of wrestling. There were moments, especially early on, when WCW also seems like that. Unfortunately, as that company slid towards its end, they lost sight of the appeal of pure wrestling in favor of even more gimmicks, swerves, and celebrity guests than WWE had.

The nadir, of course, was when actor David Arquette won the WCW World Heavyweight Championship. Arquette, a wrestling fan himself, by all accounts didn't want to win the title over all the real wrestlers in the company, but it happened anyway. In recent years, Arquette has become a respected indie wrestler in his own right, but at the time he was just a Hollywood goofball whose win damaged the prestige of the title and the company behind it.

Such a travesty could never happen in AEW, a wrestling company dedicated to making wrestling fans happy. In fact, some people criticize AEW for pandering to its fans, as if making viewers happy is a bad thing — but as long as they can avoid the specific kind of heat WCW got for booking the David Arquette win, and avoid a few financial pitfalls along the way, they ought to do just fine.