12 Wrestling Promotions That Tried To Compete With The WWE And Failed

Many have remarked that competition breeds excellence, and this could not be more true than in professional wrestling. When two promotions go head-to-head with one another, it often provides a little extra motivation for the talent to put on the best show they can. Usually, one of the two promotions matched against one another is WWE. Former WWE Executive Vince McMahon is notorious for his competitive spirit, and was never one to shy away from a good fight. McMahon welcomed the challenge from Ted Turner in the '90s, and overcame adversity to become the industry leader in sports entertainment.

From then on, many have tried and failed to compete with McMahon and WWE. After all, having a target on one's back just comes with the territory of being the best. The longer a company or sports team resides at the top of the mountain, the bigger their target typically becomes. Some attempts at taking down WWE have been more well thought out than others. Tony Khan's All Elite Wrestling has given the folks at WWE something to think about, even if they are not yet stiff competition for the wrestling conglomerate. AEW has at least managed to give WWE fits in the key demographic, but for every AEW there are three more wrestling promotions who put WWE in their crosshairs just to get a quick rub. Regardless, several have felt the full consequences of what happens when they tug on Superman's cape.

Here are wrestling promotions that tried to compete with the WWE, only to fail in that endeavor.

World Championship Wrestling

World Championship Wrestling gave the WWF fits at several different points during its illustrious run, even dating back to its Georgia Championship Wrestling roots. Ted Turner, the network media tycoon, had long been a fan of professional wrestling, according to longtime WCW talent Sting in his appearance on the "AEW Unrestricted Podcast." "I remember Ted Turner meeting with us and saying, in the very beginning, 'you know, I got all the suits and ties around me and they complain about you guys,'" Sting said." "They don't like you wrestlers because we're always in the red. But you know what I tell them? I tell them I love wrestling and I got some deep pockets."

Turner began his relationship with GCW in 1982 when his satellite television station, WTCG (later TBS), picked up the broadcasting rights to its television show. July 14, 1984, which would become known as the infamous "Black Saturday," saw Vince McMahon attempt to lay waste to his competition. McMahon purchased majority control of the Georgia territory from the Brisco brothers and with it the company's TBS timeslot. When ratings stagnated, McMahon sold the timeslot to Charlotte, North Carolina promoter Jim Crockett Jr., who installed "The American Dream" Dusty Rhodes as the head booker of Jim Crockett Promotions.

JCP and the WWF went to war between 1987 and 1988 over a series of sabotaged pay-per-view events by the WWF. Despite an overall national enthusiasm for the sports-based presentation of JCP, Crockett was hemorrhaging money, opening the door for Turner to step in and buy the company in 1988. Turner renamed the company to "World Championship Wrestling," and sought to make it one of the country's premier television attractions. Turner eventually hired young and unproven Eric Bischoff as Executive Producer. Bischoff surprised in the role and his initially frugal ways saved the company truckloads of money as they looked to create a positive profit margin. Bischoff later had free reign to spend on stars like Randy Savage, Hulk Hogan, Ric Flair, Scott Hall, and Kevin Nash, setting the stage for the Monday Night Wars. The edgier WCW product beat McMahon's WWF in the ratings for 83 consecutive weeks, forcing the typically cartoonish WWF to adapt in order to survive. The rise of stars like The Rock and Steve Austin helped the WWF regain momentum throughout the late '90s, and Bischoff's laissez-faire locker room began to fall apart at the seams. McMahon purchased his competition in 2001, but the idea of two wrestling companies going head-to-head on Monday nights will forever be remembered as a '90s cultural phenomenon.

Universal Wrestling Federation (Bill Watts)

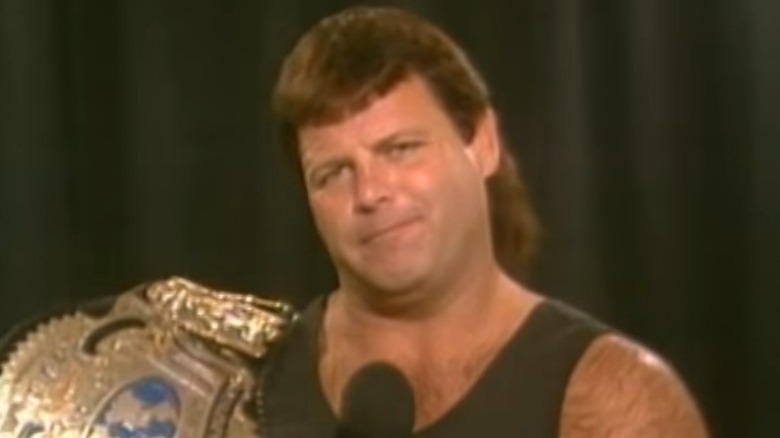

"Cowboy" Bill Watts took a couple of turns at competing with the WWF. Watts booked WCW between 1992 and 1993, but his old-school ways failed to catch on. Prior to this, Watts was best known for leading Mid-South Wrestling between 1979 and 1986. After years of operating as one of the premier American wrestling territories, Watts opted to take the promotion national after years of flirting with the idea. In doing so, Watts joined a group of several promoters jockeying for pole position as the WWF's top competitor. The newly-named Universal Wrestling Federation landed a syndication deal that saw the program aired in major markets around the United States.

While the shows were well-received, Watts simply did not have the distribution to compete with the WWF and Jim Crockett Promotions, which had successfully positioned itself as the WWF's top competitor. A recession in the oil industry of Oklahoma also stunted UWF's growth, as many of the promotion's blue-collar fans had less disposable income to use to attend shows. JCP swallowed the UWF on April 9, 1987 after Watts sold the company to Crockett. Some of its top stars, such as the Fabulous Freebirds, Eddie Gilbert, and "Dr. Death" Steve Williams caught on immediately with the Crockett fan base. The UWF purchase is also how Sting came to join the fold in Atlanta, as he and his tag team partner, The Ultimate Warrior, had UWF deals. The Warrior would not be retained, however.

Universal Wrestling Federation (Herb Abrams)

Bill Watts' UWF was not the only Universal Wrestling Federation to exist pre-1997, nor was it the only company of the same name to have a syndication deal. Herb Abrams, an eccentric New York City business owner, founded his take on the UWF in 1990 to try and compete with the WWF on a national scale. Since Watts never trademarked the name UWF, Abrams adopted the name for his new wrestling company. The man once known as "Mr. Electricity" unveiled the new promotion at John Arezzi's Wrestling Fans Fantasy Weekend convention in August 1990. Despite having no experience in the wrestling business, Abrams finessed SportsChannel America into giving him $1 million to develop a weekly wrestling television series according to author Jonathan Plombon in his Abrams biography, "Tortured Ambition: The Story of Herb Abrams and the UWF."

Despite Abrams being hellbent on his desire to compete with the WWF, the industry leader refused to acknowledge Abrams and his promotion. As a result, Abrams started booking contracted WWF talent to appear on his shows such as the Honky Tonk Man, even if he couldn't afford to pay him. The WWF also squashed Abrams' attempt to sign Andre the Giant to a long-term deal. In spite of the WWF's unwillingness to play ball with the UWF, Abrams somehow finagled his way into a meeting with Vince McMahon to discuss promoting WWF live events on the west coast. According to Plombon, Abrams was blown off. Abrams' delusions of grandeur — as well as his impulsiveness and personal vices — doomed the UWF from the start, but not before he managed to get stars like Cactus Jack, Paul Orndorff, and Chief Jay Strongbow in the building.

The story of Abrams and his promotion has come to renewed prominence in recent years, with Vice's "Dark Side of the Ring" airing an episode centered around Abrams in May 2020.

Extreme Championship Wrestling

Paul Heyman's Extreme Championship Wrestling may not have had the financial backing necessary to seriously compete with the WWF, but that did not stop him from convincing his locker room of wrestlers they could. "What was it like competing in the single most hyper-competitive environment in the history of this industry? With absolutely no sponsors, no advertisers, no big money-backers or trust-funds behind me? It was exhilarating," Heyman told Sports Illustrated. Owned by Philadelphia jewelry store owner Tod Gordon, ECW had been formerly known as Eastern Championship Wrestling, a subsect of the new National Wrestling Alliance, and became a force in the tri-state area under booker Eddie Gilbert. However, Heyman won a power struggle with Gilbert and officially took over as booker in late 1993. One year later, Heyman convinced Shane Douglas, the newly-minted NWA World Heavyweight Champion, to throw the belt down during a post-match promo, ushering in the era of "extreme."

ECW brought a new style of wrestling presentation to the mainstream, combining traditional pro wrestling with car-crash television to create a countercultural product. Heyman mastered the art of highlighting the strengths of his wrestlers and could just as easily hide their weaknesses. A solid blend of misused wrestlers from the two major federations and homegrown talent made up the roster, and the promotion began to grow organically under Heyman's creative direction. Raven detailed Heyman's motivational tactics in the Kayfabe Commentaries release, "Timeline: A History of ECW 1996, as told by Raven," praising Heyman's ability to squeeze the best out of his talent while positioning the WWF and WCW as the "enemy." (ECW went on to work with the WWF in an official and unofficial capacity in 1997.) Despite landing a television deal with TNN, ECW eventually filed for bankruptcy while Heyman found his way into backstage and on-screen roles with the WWF.

American Wrestling Association/Pro Wrestling USA

Verne Gagne, a Minnesota wrestling legend, looked to expand nationally to compete with the WWF. Gagne, who owned the American Wrestling Alliance based out of Minneapolis, saw success with western expansion throughout the '70s. The company thrived off the back of matches between Superstar Billy Graham and Wahoo McDaniel, and as a syndicated program went on to create more stars in the early '80s such as Nick Bockwinkel and Rick Martel. The AWA even had Hulk Hogan for a pre-Hulkamania three-year run. However, the AWA soon became a victim of its own success, as Hogan, along with fellow talent such as "Mean Gene" Okerlund and Bobby "The Brain" Heenan, would be lured to New York with lucrative deals.

In an effort to combat the WWF's expansion, Gagne got together with Jerry Lawler and Jerry Jarrett of Continental Wrestling Association, Ole Anderson of the revived Georgia Championship Wrestling, Jim Crockett, and other NWA promoters to co-promote wrestling shows nationally, according to "Ringside: A History of Professional Wrestling in America." The joint venture known as Pro Wrestling USA began in 1984, but would not last, as dissension among the ranks began to consume the alliance. Gagne accused JCP's David Crockett of attempting to sign his AWA talent to exclusive deals and the venture quickly fell apart in 1986.

Meanwhile, the AWA began to lose influence in the local area due to the success of the original WrestleMania, though the company did gain a timeslot on the nationally broadcast ESPN Classic. As territory wrestling began to go the way of the dinosaurs, Gagne filed for bankruptcy in 1991. "When we got all the promoters together and did USA wrestling [Pro Wrestling USA], if they would've had one man make the decision and they go by that, but they all had their egos and they were all battling all the time," Greg Gagne said in an interview with "The Two Man Power Trip of Wrestling Podcast" (h/t ProWrestling.net). "If they would've just said, okay, Bill Watts, or Verne [Gagne], or [Jerry] Jarrett, you're in charge, whatever you'll be, you'll have the final say. They couldn't do that."

United States Wrestling Association

No promoter took as many swings at the WWF over the years as Jerry Jarrett, who was involved with the creation of Pro Wrestling USA and later Total Nonstop Action Wrestling. He even attempted to buy WCW in 2001 when the company was on its last legs. However, Jarrett also took a chance on national expansion with his Memphis-based promotion, Continental Wrestling Association. With Dallas' World Class Championship Wrestling operating in dire financial straits, Jarrett stepped in to purchase controlling shares of World Class, then merged the promotion with the CWA to create the United States Wrestling Association (USWA) in 1989. The USWA promoted shows in both Tennessee and Texas and sought to occupy real estate in the vacuum left by the dissolution of Pro Wrestling USA, with which both the CWA and WCCW were involved. Jarrett had initially looked to merge the CWA with the AWA, but negotiations fell through on the Gagne side.

The USWA in its intended form would be short-lived, as World Class pulled out of the deal less than a year into the merger. The Von Erich Family still owned 40% of WCCW at the time of the merger, and Kevin Von Erich filed a lawsuit against Jarrett and television executive Max Andrews, alleging that they were concealing funds from the family. Rather than fight the lawsuit, Jarrett continued to operate the USWA without the support of WCCW, and did so to mixed results. The USWA wound up entering a talent exchange deal with the WWF that paved the way for local legend Jerry "The King" Lawler to sign up north. In exchange, bankable WWF stars occasionally appeared in the USWA while the promotion became the first de facto developmental territory for the company. The Rock wrestled matches in USWA under the name Flex Cavana, and the USWA also served as a playground for Vince McMahon to test out the "Mr. McMahon" character before closing doors in November 1997.

World Wrestling All-Stars

Upon the closure of WCW, two promotions immediately sprouted, looking to fill the giant void left by Ted Turner's old company. Australian music promoter Andrew McManus' WWA will go down as the first and most significant of the two, as it served as the true link between WCW and what became TNA. McManus focused primarily on signing wrestlers who went unsigned by the WWF following the purchase of WCW, as well as other name talent ready to work immediately. He also installed Jeremy Borash as lead booker at the recommendation of Vince Russo. The roster included names such as Jeff Jarrett, Road Dogg, Scott Steiner, Sting, Rick Steiner, Shane Douglas, Buff Bagwell, Lex Luger, and Sabu. Bret Hart even made an appearance as an authority figure. The first tour covered dates across Australia, but the ensuing debut pay-per-view in Sydney proved to be a considerable flop due to the brevity of matches and overall disorganization.

The debut show in Sydney set the tone for WWA's inevitable fate. The company went on to run one stateside event, "The Revolution," at the Aladdin Casino in Las Vegas (now Planet Hollywood). The lacking quality of the shows combined with the fluctuating state of the wrestling business ultimately did in WWA before it ever being able to compete with the WWF. However, the company's brief existence did prove there was enough room in the space for a viable alternative to WWF programming. "If Andrew McManus hadn't invested in those four or five tours, I don't believe my career would have headed in the direction it took," TNA co-founder Jeff Jarrett said on an episode of his podcast, "My World with Jeff Jarrett."

Xcitement Wrestling Federation

At around the same time McManus' World Wrestling All-Stars began to formulate, a second promotion called Xcitement Wrestling Federation (originally the X Wrestling Federation) came to be when entrepreneur Kevin Harrington pitched the idea to Hulk Hogan and his friends. Harrington seemed to have the financial backing to give the company legs and even anointed manager Jimmy Hart as company president. While the company shared most of its talent with World Wrestling All-Stars, it did carry some unique names such as Hogan, the Nasty Boys and Greg Valentine, with Tony Schiavone and Jerry Lawler on commentary, "Mean Gene" Okerlund as an interviewer and "Rowdy" Roddy Piper as commissioner.

The XWF took on a slightly different business model than WWA, instead opting for a more traditional television-based approach. The promotion ran two tapings on November 13 and 14, 2001 from the soundstage in Orlando's Universal Studios ... but given the minimal amount of interest in WCW at the time of its closure, Harrington quickly saw the lack of upside in his investment and pulled out of the deal leaving full control to Hart. Before Hart could enter any serious talks with networks, Hogan inked a deal to return to the WWE, causing the company to die a peaceful death. Hart purchased the rights to the footage from the tapings in 2004, and released a three-disc DVD series titled, "In Your Face: The Lost Episodes of the XWF" in 2005.

Global Force Wrestling

Though he played a crucial role in the creation and sustainability of TNA Wrestling, Jeff Jarrett left the Panda Energy-owned company in 2014, paving the way for him to create the next TNA. Through Global Force Wrestling, Jarrett sought the help of major independent promotions around the globe, creating a de facto territory system to help carry the company in its infancy. One early move saw Jarrett organize a deal with NJPW to broadcast the ninth installment of Wrestle Kingdom in the United States with Jim Ross and Matt Striker providing English commentary. Jarrett also entered a working agreement with AAA in Mexico and booked several set of tapings for "Amped," the tentative name for the company's weekly TV show, at the Orleans Arena in Las Vegas. GFW filmed 16 one-hour episodes of "Amped" between July and October of 2015 with the intention of selling the show to a network seeking pro wrestling content.

After being unable to land a television deal stateside, Jarrett ended up back with TNA (now Impact Wrestling) in the role of chief creative officer. Jarrett seemed happy to be back in his old company, telling "The Hannibal TV" that Impact and GFW were "becoming one day-by-day." Indeed, the two companies officially merged in April 2017 and even planned on rebranding the company as "Global Force Wrestling." However, Jarrett took a leave of absence from the company, paving the way for Anthem to revert to using the "Impact" branding and break away from GFW for good. Jarrett and Anthem would then engage in a series of lawsuits that wouldn't be settled until 2021. Though the company ran or co-promoted 37 live events in its brief history, internal issues also plagued Jarrett and GFW along the way, with "Double J" getting wrapped up in a supposed pyramid scheme that gave fans the option to buy bars of gold through the company website.

New Japan Pro-Wrestling

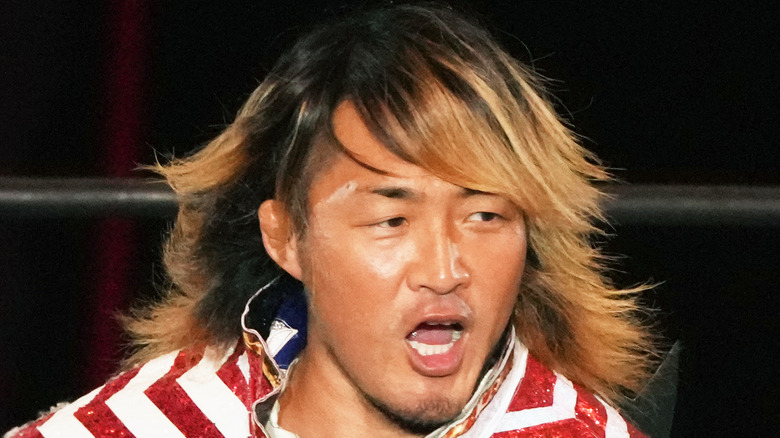

Antonio Inoki's original vision for New Japan Pro-Wrestling may not have ever involved becoming a competitor to WWE, but top wrestling company in Japan has become a thorn in the WWE's side in recent years. Popular gaijin wrestlers such as AJ Styles, Kenny Omega, and even Chris Jericho helped elevate New Japan to new heights with their performances at the Tokyo Dome, and enthusiasm for New Japan increased to the point of the company wanting to expand into North America. As a result, the company found a natural North American partner in AXS TV. NJPW signed with the network in November 2014 to air English-speaking NJPW programming on American television for the first time ever. The deal lasted for five years, and helped build to the company's first-ever stateside live events. The Long Beach shows on July 1 and 2, 2017 were the first the company had ever independently produced in North America, and the weekend of shows received significant acclaim from critics.

Partnered with Ring of Honor and AXS TV stateside, many thought New Japan could become a force in North America and eat into WWE's market share. A co-promoted G1 Supercard in 2019 became the first professional wrestling event at Madison Square Garden not promoted by the McMahon family in nearly 60 years. The WWE allegedly did everything they could to put the kibosh on the event, but issues between the three parties would be resolved ahead of the event.

All Elite Wrestling was officially announced on New Year's Day 2019, and soon after announced the signings of Omega, Jericho, and The Young Bucks — all key players in the North American market for New Japan. As a result, AEW stole much of New Japan's thunder, channeling it into its own attempt to compete with WWE. This would not deter NJPW from westward expansion, however, as they announced a new touring brand, New Japan Pro-Wrestling of America. Episodes of a new show, "NJPW Strong," stream live on NJPW World, the company's streaming service, as well as FITE TV. However, the departure of embattled company president Harold Meij led NJPW to take its foot off the gas pedal in becoming a self-sustaining operation in the west. Instead, the promotion partnered with companies such as AEW and Impact to better expose its talent to western audiences.

Wrestling Society X

Wrestling Society X came from the brain of producer Kevin Kleinrock, who pitched the idea of a wrestling promotion that could bridge the gap between in-ring action and punk rock music. MTV loved the idea and provided Kleinrock and his team the tools and money to produce a pilot season, putting WSX on a different path than some of its successors and predecessors. "This was the first wrestling-related show that was fully funded by a television network," Kleinrock told Rolling Stone. "This isn't us creating a wrestling organization and taking it to the network, like most others. This is us working with the network to create a wrestling series for the network."

Unfortunately for Kleinrock and WSX, MTV's influence began to overwrite Kleinrock's original vision for the show. The Viacom-owned channel presented WSX as a secret wrestling society where falls could be counted anywhere in the arena. Certain ideas, like the show's concept and episodic nature, later served as the basis for Lucha Underground, a true wrestling alternative. That said, there were many problems with the format. Episodes were limited to just 30 minutes, severely handicapping the possibilities in the ring while keeping matches to roughly three minutes in length. Those three minutes included the possibility of wacky stunts and stipulations, such as piranha death matches and explosion matches. Still, the show opened to reasonable success, drawing a 1.0 rating in the 10:30 p.m. timeslot, going head-to-head with "ECW on SyFy." However, the upstart wrestling television program could not keep the interest of viewers and would be canceled after just one season.

Total Nonstop Action Wrestling

The story of TNA Wrestling is one of a wrestling company taking on several different identities and creative visions. Jeff and Jerry Jarrett founded the company in 2002, fresh off of Jeff's involvement in World Wrestling All-Stars. From there, TNA sought to introduce a new breed of wrestlers to the mainstream wrestling audience, while operating as the clear-cut Number 2 wrestling promotion in the United States. When Vince Russo entered the creative picture, Panda Energy entered the financial picture, buying the elder Jarrett out of his shares while taking over as the controlling shareholder of the company. With solid financial backing, TNA began to stockpile former WWE talent in their primes such as Rhino, Christian Cage, and Kurt Angle, pairing them with younger talent such as AJ Styles and Bobby Roode and mainstays like Sting. As a result, the company began to grow organically, picking up a timeslot on Spike TV, the former home of "Monday Night Raw."

Though TNA casually mentioned WWE from time to time on screen, the company remained steadfast in its mission to become a viable alternative to WWE as opposed to becoming legitimate competition. Everything changed when president Dixie Carter brought in Hulk Hogan and Eric Bischoff to run creative. While TNA stood to gain some eyeballs with Hogan involved, the company — still just seven years old at the time — switched to the Monday night timeslot, putting it directly against "Raw" hoping to capitalize on the lapsed fan's nostalgia for the Monday Night Wars. The move backfired tremendously. The ratings began to dwindle, and homegrown stars such as Styles began to leave for greener pastures as the company continued to hemorrhage money. TNA lost its TV deal with Spike TV along the way and never fully recovered, with Carter being forced to sell the rebranded Impact Wrestling to Anthem, a Canadian company that still owns and operates the wrestling organization to this day.