Facts About New Japan Pro-Wrestling Only Hardcore Fans Know

New Japan Pro-Wrestling is one of the oldest wrestling promotions in the world, having celebrated their 50th anniversary in 2022. In the last several years, thanks to factors including the launch of the NJPW World streaming service, the rise and dominance of Kazuchika Okada, the explosion in popularity of The Young Bucks and Kenny Omega's The Elite stable, and guest appearances by Chris Jericho and Jon Moxley, the company has become a much bigger presence in the western wrestling world. This means that there are a lot of newer NJPW fans who don't know as much about the history of the company as those who were raised on the promotion in the era of tape trading and print wrestling newsletters gleaned over the years.

With the caveat that many of these things might be more common knowledge to more casual fans in Japan proper, that means that there's a lot of important history about the growth of NJPW that many western fans probably have no idea about. And some of it is kind of weird.

NJPW came very close to losing their TV show in 1987

New Japan Pro-Wrestling was in a constant state of flux in the mid-1980s. According to an article at IgaPro (English summary courtesy of KinchStalker at ProWrestlingOnly.com), TV ratings for their weekly prime time show on TV Asahi, "World Pro Wrestling," had dropped from about 20% to the 10% range after the departures of Tiger Mask, Akira Maeda (and his friends who formed the UWF), and Riki Choshu's Ishigundan stable in 1983-1984. By the time the spring of 1987 came around, though the UWF stars had returned, the ratings hadn't recovered, and NJPW needed something big.

"It has been reported in several Japanese newspapers that Riki Choshu will be jumping to Antonio Inoki's New Japan Pro-Wrestling promotion," wrote Dave Meltzer in the top story of the March 9, 1987 issue of his Wrestling Observer Newsletter. "Probably the most important factor, which led to all this, was the word given by TV Asahi that they were thinking seriously about canceling Inoki's weekly TV show as of early April. Inoki needed to hit a home run to save his network slot, which means Chnshu was probably given a financial offer he could hardly turn down." Even then, though, that would take time since, as noted by IgaPro, Choshu wasn't immediately able to sign a contract that allowed him to appear on TV Asahi.

Instead of being canceled, "World Pro Wrestling" transitioned into "I Can't Wait Until the Give-UP!", an NJPW-themed variety/talk show along the lines of other prime time network programming in Japan. This, predictably, did not work. The debut dropped to a 5.7% rating and week two dropped further to 5%, leading to the end of many of the variety show elements. By July, the show was almost completely back to normal as "World Pro Wrestling," and though it has long since changed to a half hour late night show, it still airs to this day.

NJPW wasn't the first startup promotion featuring Antonio Inoki

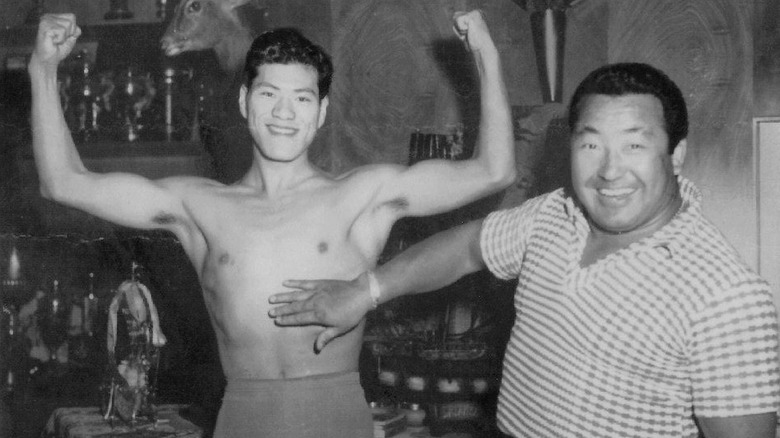

If you know Japanese wrestling history, then you probably know that NJPW formed in 1972 after Antonio Inoki broke away from the JWA, the same thing that Giant Baba did that same year to form AJPW. Less well-known, though, among western fans, is that this was not the first time that Inoki had broken away to anchor a new promotion, as he was one of the faces of Tokyo Pro Wrestling when it launched in 1966.

Per KinchStalker's English summary of information from IgaPro and print media sources, the startup was launched as a vehicle for Toyonobori, who was excommunicated from the JWA after he embezzled company funds to pay gambling debts. (Hisashi Shinma, later Inoki's business manager, would help fund the company with help from his father.) Inoki was on his "learning excursion" in the United States at the time, and both promotions tried to win his loyalty. Tokyo Pro even earmarked a ¥1 million payment for Inoki if he jumped, but Toyonobori gambled it away before he could talk with the young star.

Still, Inoki made the move, thanks in large part to his lack of faith that JWA saw much value in him. None of this lasted very long, though, as Tokyo Pro was done within a year, thanks in large part to Toyonobori's continued financial improprieties going public. Most of the roster would go to the new International Wrestling Enterprises promotion, but Inoki managed to negotiate a return to the JWA.

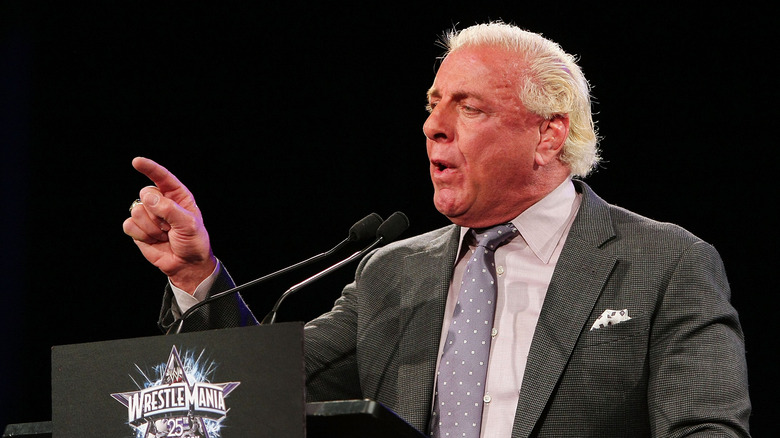

NJPW once went to their rivals to save a Tokyo Dome show after Ric Flair pulled out

For pretty much the entire time that NJPW and AJPW were helmed by Antonio Inoki and Giant Baba, respectively, they were bitter rivals. Mass jumps of talent from one promotion to the other only made the animus worse. In 1990, though, they were able to put that aside.

NJPW was set to run their second ever Tokyo Dome supercard, Super Fight, on February 10, 1990, with the two big attractions being the pro wrestling debut of sumo champion Koji Kitao (vs. Bam Bam Bigelow) and a main event of Ric Flair defending the NWA World Heavyweight Title vs. The Great Muta. A few weeks out, though, the main event fell apart. "Flair canceled the booking [...] with the given reason being that TBS was going to dock him one week's pay if he went to Japan for the show," reported Dave Meltzer in the February 1, 1990 issue of his Wrestling Observer Newsletter. Since Flair was making somewhere in the neighborhood of $750,000 per year, that made the trip a wash financially for Flair, who was also the head of the WCW booking committee at the time.

As noted in the February 5 Observer, Inoki and Baba didn't necessarily get along, but Baba and Seiji Sakaguchi — Inoki's right hand man — were friends, and with NJPW being desperate, they agreed to do business. Three of the top matches at Super Fight would now be NJPW vs. AJPW: Kengo Kimura and Osamu Kido (NJPW) vs. Jumbo Tsuruta and Yoshiaki Yatsu (AJPW), Riki Choshu and George Takano vs. Genichiro Tenryu and Tiger Mask II (AJPW), and Big Van Vader (NJPW) vs. Stan Hansen (AJPW).The move paid off, and the show sold out within a few days of the announcement.

NJPW has been banned from running shows at Sumo Hall in the past

The current Tokyo Sumo Hall (formally Ryōgoku Kokugikan) opened in 1985, and on top of its primary use, it quickly became a legendary pro wrestling venue. The Japan Sumo Association controls the building, though, and they've been sticklers, having banned AJPW from running shows there in 1987 after Giant Baba signed sumo stars like Hiroshi Wajima and John Tenta. NJPW was safe for the time being, but that would soon change.

All of this is laid out in the January 11, 1988 edition of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter, which covered NJPW's December 27 Sumo Hall card. Originally set to be headlined by Antonio Inoki vs. Riki Choshu, the card was changed as it was going on when new heel manager Takeshi Kitano challenged Inoki to fight the debuting Big Van Vader, who was advertised in a tag team match with Masa Saito vs. Tatsumi Fujinami and Kengo Kimura. "The fans didn't like this and started sensing a change in the card," wrote Dave Meltzer in the Observer. "They started throwing eggs, programs, orange juice containers and beer cans at the ring."

Choshu was inserted into the tag match, resulting in loud objections from the fans, then wrestled Inoki for six minutes before a cheap disqualification. "The fans started a mini-riot once again, because the ticket prices were so high and this match was too short and didn't have a clean finish," wrote Meltzer. It got worse after Vader squashed Inoki in under three minutes. "The fans continued to be unruly and caused so much damage in the hall that the real bad news came a few days later when the Tokyo Sumo Association banned pro wrestling from Sumo Hall." That ban would last until February 1989.

Legendary actor/director Takeshi Kitano was briefly a heel manager in NJPW

If you're a cinephile who was flummoxed by "Beat" Takeshi Kitano's involvement with NJPW, here's your explanation. The actor/comedian/director/talk show host was not having a great year in 1987. As the South China Morning Post explained on January 2 of that year, he had been somewhat publicly disgraced by the news that 39 year old Kitano and 11 friends ("his gang, the Takeshi Gundan") had "stormed" the offices of Friday, a gossip magazine and assaulted the staff after they "reported on the doings of his 21-year-old college student girlfriend." He was suspended from appearing on TV, and when he returned, naturally, he landed in professional wrestling.

Per a 2017 article from Last Word on Sports, the gist was that, to take out Antonio Inoki, Kitano enlisted Masa Saito to build him a new gang, Takeshi Puroresu Gundan, with Saito enlisting Riki Choshu, the debuting Big Van Vader, and trainees who would later become Gedo, Jado, and Super Delfin. The involvement of the trainees suggests some long-term plans, but that's where everything starts to get hazy because the storyline was quickly dropped after the Sumo Hall riot.

It's hard to pin down if the trainees were plucked from NJPW's dojo, recruited separately, or what, but they soon found themselves without a home and were blessed by the sheer luck that Japan's independent scene was about to start blowing up. Vader, of course, managed to rise above the disaster and become a massive star in Japan.

NJPW ran five separate dome show supercards in 10 months in 1997

Business was booming big time in 1997 for New Japan. How big? With the Osaka Dome and Nagoya Dome both opening that year and the tradition of shows at the Tokyo Dome and Fukuoka Dome going back several years, it was to be the year of the domes, with a whopping five stadium shows that year (Tokyo got two).

Per the March 3, 1997 issue of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter, the spring dome shows were originally going to kick off with IWGP Heavyweight Champion Shinya Hashimoto defending his title against the debuting Ken Shamrock, but Shamrock went to the WWF instead. Needing a new "shooter" to replace the former UFC Superfight Champion, NJPW enlisted Naoya Ogawa, a 1992 Olympic silver medalist in judo. To establish Ogawa as a star, he upset Hashimoto in their initial non-title match in Tokyo, only to lose the rematch in Osaka. It worked: They packed both domes, and the other three dome shows that year (January's first Tokyo show plus the August Nagoya and November Fukuoka shows) drew big crowds with more standard NJPW supershow fare.

Though Hashimoto had firmly established himself as New Japan's top star and biggest draw in 1996, it was the "year of the domes" that really put him over the as the hall of fame level legend that he's considered today.

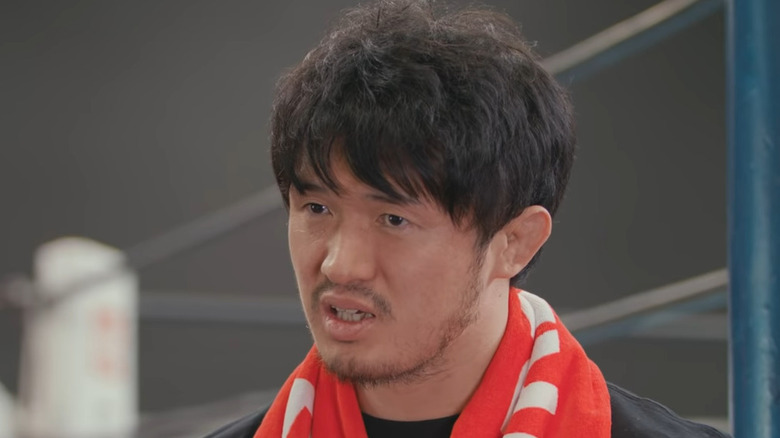

The current LA Dojo is not NJPW's first such effort

NJPW's dojo in Los Angeles, headed by Katsuyori Shibata, has gained much attention. Viewers of NJPW Strong are exposed to the L.A. Dojo graduates constantly, with the likes of Clark Connors, Ren Narita, and Yuya Uemura being among the best of the crop. This L.A. Dojo, however, is not NJPW's first L.A. Dojo.

In the early 2000s, when Antonio Inoki's cross-pollination of pro wrestling and mixed martial arts was getting increasingly weird and thorny, he opened up a dojo in Los Angeles, Inoki Dojo, where various wrestlers and fighters would train. "Mr. Inoki was always such a mystery –- and I'm not talking his in-ring character," local promoter David Marquez told Monthly Puroresu in 2022 for a feature about the old dojo. "I feel he enjoyed training the young talent very much, but [he didn't share] a clear vision for the L.A. Dojo ... although, I do feel [his son-in-law] Simon had a roadmap and we did our best to follow it."

As noted by SoCal Uncensored in 2017, the list of wrestlers who came through the Inoki Dojo as wrestlers and coaches is pretty impressive: It boasts, among others, Bryan Danielson, Samoa Joe, Shinsuke Nakamura, Rocky Romero, Ricky Reyes, T.J. Perkins, Chad Collyer, and even Chyna. Most of the Americans would get shots in NJPW proper, with Samoa Joe being the notable exception as he worked for rival promotion Zero-One at the time.

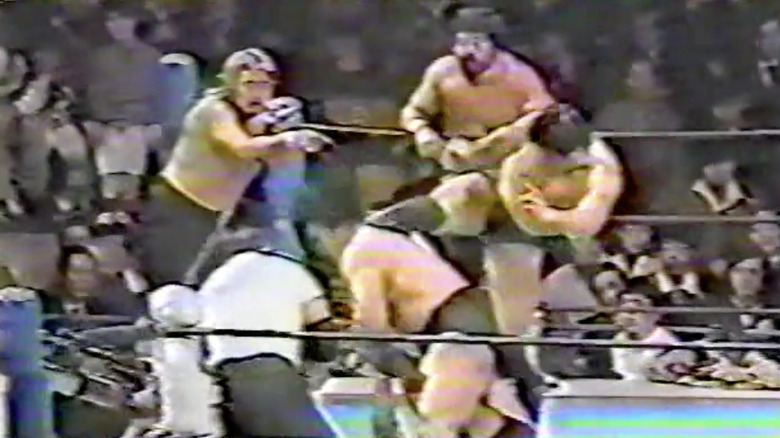

One of their top stars deliberately sabotaged his NJPW career by shooting on a colleague

1987 was a strange year for NJPW, and that's without even mentioning things like the hours-long Antonio Inoki vs. Masa Saito match on a deserted island. It continued to be weird as the year started to draw to a close, thanks to the actions of Akira Maeda at the November 19 card at Korakuen Hall in Tokyo. Maeda, Nobuhiko Takada, and Osamu Kido were battling Riki Choshu, Masa Saito, and Hiro Saito. The Maeda-Choshu interactions were awkward, with Maeda not selling much for Choshu. Eventually, Choshu started applying the Scorpion Deathlock on Kido with his back to the opposing corner. Maeda casually entered the ring, sauntered over to Choshu, and threw a full force kick to his face. Seconds later, Choshu, his eye swelling shut, realized what happened, and the match fell apart.

"Choshu and Maeda's egos clashed. Maeda wanted to rebuild the UWF as an organization, but it was being taken over by New Japan, so I think he had a sense of crisis," fellow NJPW legend Tatsumi Fujinami told Number in 2022 (roughly translated using DeepL). To make matters worse, as Dave Meltzer explained in the December 21, 1987 edition of his Wrestling Observer Newsletter, it would be tricky for NJPW to address the situation publicly. "[H]ow can you explain suspending someone for a kick to the face when in every match, wrestlers kick to the face," he wrote. Regardless, this worked out perfectly for Maeda, as he could claim that he was too real for pro wrestling and launch a new UWF promotion that purported to be a real deal.

Well, that is unless you believe his claim, featured in a 2021 IgaPro article, that it was an accident and Choshu accidentally turned into the kick.

One of NJPW's most legendary feuds was almost ruined by spite

The second UWF closed in 1990, with its closest spiritual successor being Nobuhiko Takada's UWFi, which was successful ... until December 1994. As Dave Meltzer explained in the August 29, 2011 issue of his Wrestling Observer Newsletter, the UWFi sent Yoji Anjo — flanked by photographers — to California to challenge Rickson Gracie to a fight at his school after he'd become a superstar winning a legitimate MMA tournament in Japan. Rickson, naturally, mauled Anjo, whose bloody face adorned magazine covers. "When Takada was quiet instead of publicly challenging Gracie after beating up one of his star wrestlers, the edge was off the UWFI group," Meltzer added in 2011.

With the UWFi going down the tubes, there was only one clear option: Make a deal with NJPW for an interpromotional feud. One problem with that: The UWFi had pulled other grandstand challenge stunts at NJPW's expense. As a 2022 Number article explains, stunts like sending UWFi rep/wrestling legend Lou Thesz and media to NJPW's offices with a contract for a champion vs. champion match meant that tensions were high. "They are a disgrace to the wrestling world", Number quotes then-NJPW booker Riki Choshu as saying (roughly translated using DeepL). "When they go down, I'll s**t on their graves!"

On October 9, 1995 at the sold-out Tokyo Dome, NJPW almost completely ran the table, winning five of the seven matches booked by Choshu. Making matters worse, Keiji Mutoh won the main event by making Takada submit to a figure four leglock, described by Meltzer in the Observer days later as "a move not even considered legitimate in [the] UWF." Despite Choshu's spite booking, the feud continued to sell tickets, though: In the January 15, 1996 Observer, after the Mutoh-Takada rematch sold out the Tokyo Dome again, Meltzer proclaimed it the biggest-drawing feud in wrestling history up to that point.